Before visiting southeastern France, the only image I had was of Provence’s lush lavender fields and rolling hillsides. Although I didn’t visit any lavender fields, I did experience several vineyards in the Côtes du Rhône subregions of Tavel and Châteauneuf-Du-Pape. These two wine appelations have their unique claims to fame in the wine industry, but they share one very important element — their terroir — that wonderful word that encompasses everything from the ground-up and all the atmospheric, geographic and historic influences in-between. If you are a history/geography nerd like me, I hope you will find what I learned about the terrior of these regions as enlightening as I did.

Before visiting southeastern France, the only image I had was of Provence’s lush lavender fields and rolling hillsides. Although I didn’t visit any lavender fields, I did experience several vineyards in the Côtes du Rhône subregions of Tavel and Châteauneuf-Du-Pape. These two wine appelations have their unique claims to fame in the wine industry, but they share one very important element — their terroir — that wonderful word that encompasses everything from the ground-up and all the atmospheric, geographic and historic influences in-between. If you are a history/geography nerd like me, I hope you will find what I learned about the terrior of these regions as enlightening as I did.

Upon landing at the Marseilles-Province Airport (MRS) and taking a short one hour, forty-five minute bus ride, you witness firsthand the arid landscape of southeastern France. There’s a lot of sand, not too many trees and lots of rock and small brushes covering the hillsides.

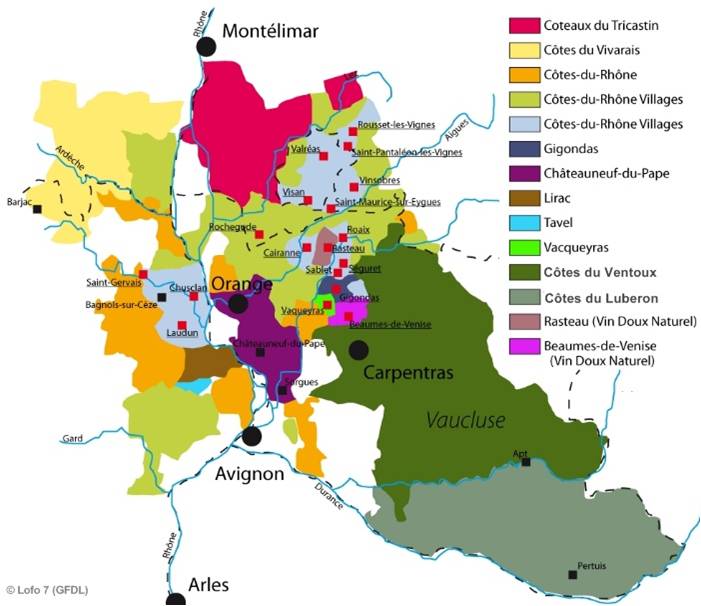

Upon landing at the Marseilles-Province Airport (MRS) and taking a short one hour, forty-five minute bus ride, you witness firsthand the arid landscape of southeastern France. There’s a lot of sand, not too many trees and lots of rock and small brushes covering the hillsides.  It’s like comparing south Florida to the Midwest United States, just a totally different, more diverse and spicey atmosphere than say Paris. “Côte” is French for hills or slope. Hence the Côtes du Rhône describe the rolling topography found along the Rhône River valley. Côtes du Rhône is a wine-growing Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) for the Rhône wine region of France. So Chateauneuf du Pape and Tavel are sub- or special AOCs within the umbrella group of Côtes du Rhône wines that are found in the more southern part of the Rhône-valley area, around the cities of Orange and Avignon. Besides, the arid Mediterranean climate, there are two key terroir attributes of the Côtes du Rhône wine region that make it unique in comparison to the rest of the world – garriques and the soils.

It’s like comparing south Florida to the Midwest United States, just a totally different, more diverse and spicey atmosphere than say Paris. “Côte” is French for hills or slope. Hence the Côtes du Rhône describe the rolling topography found along the Rhône River valley. Côtes du Rhône is a wine-growing Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) for the Rhône wine region of France. So Chateauneuf du Pape and Tavel are sub- or special AOCs within the umbrella group of Côtes du Rhône wines that are found in the more southern part of the Rhône-valley area, around the cities of Orange and Avignon. Besides, the arid Mediterranean climate, there are two key terroir attributes of the Côtes du Rhône wine region that make it unique in comparison to the rest of the world – garriques and the soils.

Garriques refer to the aromatic plants that grow throughout the region as natural, wild, local brush. These plants provide the staples to southern French cuisine and contribute to the distinct flavors found in Rhône wines. Wild rosemary, sage, thyme, and bayleaf plants sprout in valleys, along slopes and atop the hills.

Garriques refer to the aromatic plants that grow throughout the region as natural, wild, local brush. These plants provide the staples to southern French cuisine and contribute to the distinct flavors found in Rhône wines. Wild rosemary, sage, thyme, and bayleaf plants sprout in valleys, along slopes and atop the hills.

Côtes du Rhône’s special soils were created by the Rhône River not decades or centuries ago, but millennia! The Rhône River originates in the Swiss Alps, upstream from Lake Geneva. Millions of years ago, the Rhône Glacier carved an incredibly wide swath on its way south with rivers running deep within it. The combination of ice grinding and waters flowing left behind a wealth of soil varities across the span of the present day Côtes du Rhône region. You have to try to envision that the Mediterranean Sea encircled the Alps millions of years ago. Only the Caspian and Black Seas remain today. The ancient glacier left a land primed with fertile vineyards composed of three soil types which are collectively referred to as “mother stone.”

Limestone is a sedimentary rock composed of skeletal fragments of marine

Limestone is a sedimentary rock composed of skeletal fragments of marine organisms. The limestone of the Côtes du Rhône region is comprised of basilica and silica quartite. The limestone is sharp and dense like granite. Limestone’s mineral composition provides more sharp notes or tannins to red wines. Also, vines are forced to grow through cracks in the limestone which gives more more bitter and complex character to the resulting, battle-worn wines. However, the cracks are often filled with clay which assists in retaining much needed moisture during the region’s frequent droughts.

organisms. The limestone of the Côtes du Rhône region is comprised of basilica and silica quartite. The limestone is sharp and dense like granite. Limestone’s mineral composition provides more sharp notes or tannins to red wines. Also, vines are forced to grow through cracks in the limestone which gives more more bitter and complex character to the resulting, battle-worn wines. However, the cracks are often filled with clay which assists in retaining much needed moisture during the region’s frequent droughts.

“Galet roulé” or rolling stones are the second soil variety. These beautiful stones come in hues of red, orange, yellow and multitudes of brown shades. Typically quartzite, these are the remnants from when the glacier chewed-up the bedrock and spat it out in the form of rocks and clay. Galet roulé are rounded and smooth on all sides like river rocks having been rolled and washed over for millennia by the Rhône River. Galet roulé can also be translated as “pebbles,” but Americans would never use this term for such large stones. Some are even the size of small boulders. A benefit of the galet roulé is its retention of heat during the day and gradual release of it through the night. This keeps temperatures in the vineyard fairly constant and assists in a steady ripening of the grapes. The stones can also serve as a protective ground covering to help retain moisture in the soil during dry spans in the weather.

“Galet roulé” or rolling stones are the second soil variety. These beautiful stones come in hues of red, orange, yellow and multitudes of brown shades. Typically quartzite, these are the remnants from when the glacier chewed-up the bedrock and spat it out in the form of rocks and clay. Galet roulé are rounded and smooth on all sides like river rocks having been rolled and washed over for millennia by the Rhône River. Galet roulé can also be translated as “pebbles,” but Americans would never use this term for such large stones. Some are even the size of small boulders. A benefit of the galet roulé is its retention of heat during the day and gradual release of it through the night. This keeps temperatures in the vineyard fairly constant and assists in a steady ripening of the grapes. The stones can also serve as a protective ground covering to help retain moisture in the soil during dry spans in the weather.

The third and final soil variety is sand. The former Rhone riverbed is now dry and finely grained, white silica. In contrast to the other soils, the sand provides an unhindered foundation for roots to grow. Without the struggle against rocks and galets, vines are relaxed and produce softer, more mellow wines.

On the surface, these three soils are very distinct. However, it is important to note that different layers of each occur in varying depths and combinations across the landscape. So, what appears to be galet roulé on the surface may have a thick bed of sand laying one meter below. Within the Côtes du Rhône region, sub-region, and even parcel-by-parcel, the variations of these three soils, in addition to garrique bushes and climatic variations in rain and temperatures, create an endless array of influences upon every harvest and annual wine production. There is no one typical terrior for the Côtes du Rhône region, just as there is no single, signature wine variety — thanks to the primordial Rhône Glacier/River.

Disclosure: I tasted the wines of Châteauneuf-Du-Pape and Tavel as a part of a sponsored press trip of the region, organized by FÉDÉRATION DES SYNDICATS DES PRODUCTEURS DE CHÂTEAUNEUF-DU-PAPE & Syndicat Viticole de l’Appellation Tavel, along with 12 other wine, gastronomy and tourism bloggers from several countries. My travel and accommodations were provided by the sponsors.